“This U-turn on green investment is both disappointing and nonsensical. Ultimately we are in a rapidly escalating climate crisis and we need politicians to have courage and get on with sorting out policies to avoid the worst case outcomes and prepare the country for the serious impacts that are already unavoidable,” said Leo Murray, co-director of climate charity Possible.

“Fortunately, almost everything that needs investment up front is going to save us huge sums of money over the long term, from wind and solar farms to home insulation to electrification of railways, cars and heating.”

The other context behind the policy is the UK’s lagging economy – investing £28bn would be a shot in the arm, while also helping us meet climate targets, argued Bob Ward, policy and communications director at LSE’s Grantham Institute.

“Over the past 30 years or so the UK has been investing far less than any of its G7 counterparts, and that largely explains why the UK has been struggling to improve productivity and growth”, Ward told The Big Issue.

Britain risks falling behind other countries’ growth plans – whether Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, or similar schemes in Europe and China. The country should be investing an extra 3% of its GDP – or £77billion a year – to get up to speed, Ward said, with around £26billion coming from public investment in climate change and biodiversity.

“The argument that the economy’s doing worse than we thought is not a reason to weaken on investment,” he said.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Uncertainty over the pledge may also deter private investment, which thrives on stability. Wittingly or not, Labour’s wavering sends signals about what it might be like in office, Ward added.

“Private investors will only invest if they think the government is serious and clear about its intentions”

Without the investment, Ward said Labour “has the same problem as the conservatives – it doesn’t have a credible plan for boosting investment, and so will be stuck continuing with the rut we’re currently in.

“The Conservatives are stuck in a death spiral with the far right of its party who are climate change deniers and don’t care about the environment. They’ve seized the initiative following the Uxbridge by-election result which was not exactly a spectacular victory.

“Labour doesn’t have the courage to stand up against that narrative”

‘It was becoming a stick to beat the Labour party with’

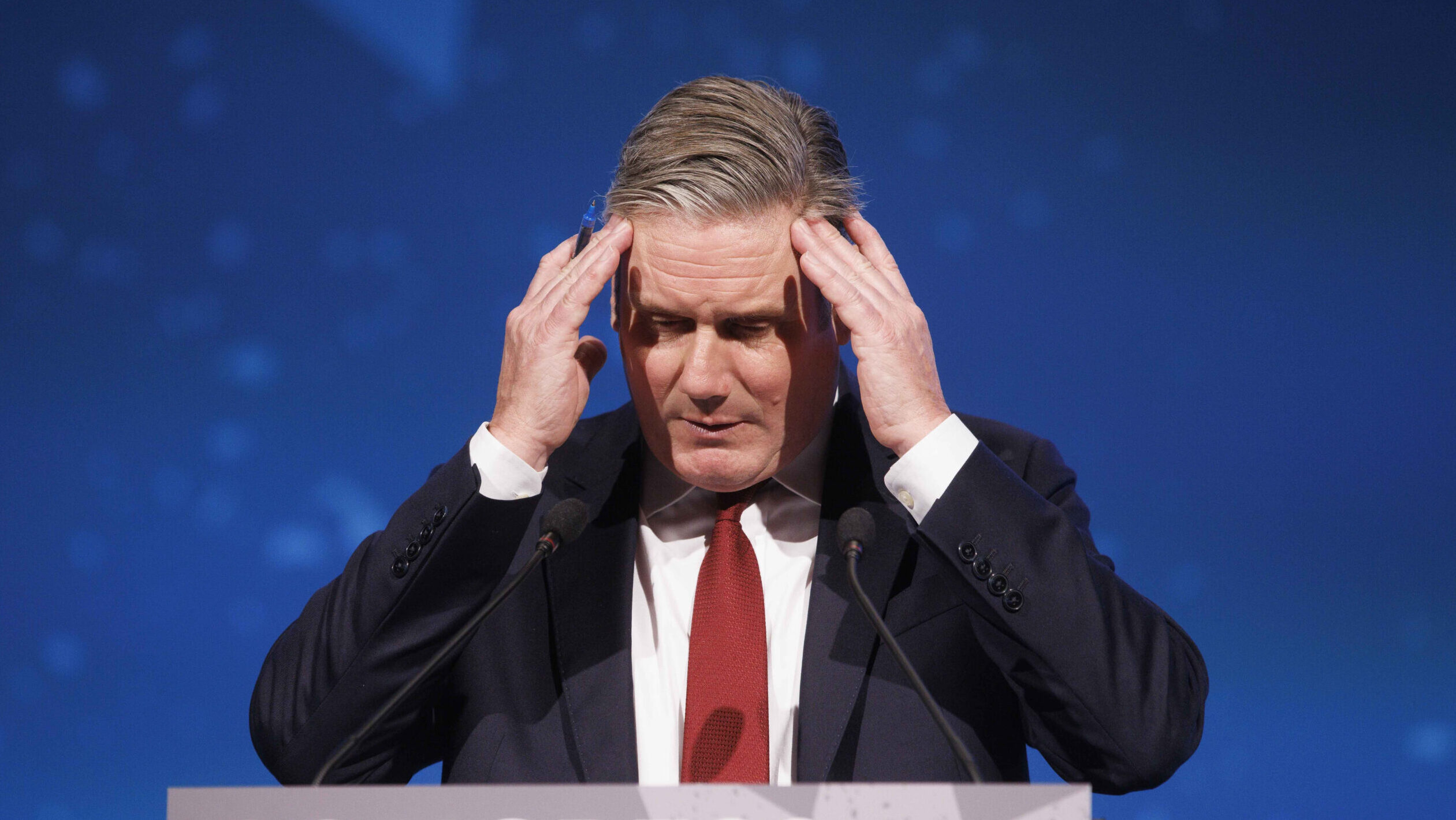

Of course, Keir Starmer is not actually the prime minister yet. Despite a huge poll lead, any policies are hypothetical unless Labour can win an election.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“The Tories kept wheeling out that particular figure, and it was becoming a stick with which to beat the Labour party every single day,” said Tim Bale, professor of politics at Queen Mary, University of London. “I think in the end they just judged it as too politically toxic in the belief that it will allow the tories to paint them as profligate and untrustworthy.”

In the short term, voters on Labour’s left may flirt with the Lib Dems and the Greens. “But come the election, the priority for most of those people is to get the Tories out, and if that means voting Labour they probably will,” said Bale.

Starmer made himself a hostage to fortune by announcing a specific figure, but also committing to stick to the Conservatives’ fiscal rules if he enters government, Bale added. “It’s an object lesson in some senses for political parties not to be too precise two years or three years out from an election,” told The Big Issue. Instead, Starmer could have laid out strong ambitions, with a more vague figure to be specified closer to the election.

There are parallels with Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s ascent to power in 1997, when the pair committed to following Conservative economic constraints. However, ditching the policy now does not mean investment cannot return if Starmer gets the keys to the nation’s most famous front door.

“It’s pretty much par for the course for governments coming in from opposition to say we looked at the books, it’s much worse than we thought, we’ll have to take stronger and more radical action than we thought we might have to,” Bale said.

For example, David Cameron and George Osborne made far deeper cuts than they had promised. “It’s not impossible to imagine Labour will play it the other way,” said Bale.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Ultimately, broad narratives around political parties matter. Coming across like a low-risk economic option matters, but there is a downside, said Bale.

“There is a concern there about whether they are offering enough inspiration and hope for people, and whether they’re drawing a sufficient difference between them and the Conservatives.”