When the first Arab Spring protests started to happen, I was in London, scouring Arab social media for any news. Mainstream Western media hadn’t yet picked up the story, and by the time it did, there was one narrative that underpinned the reporting – oppression in the Arab world had become so bad that something had burst. A man lit himself on fire in Tunisia and became a symbol for frustrated Arab people across the region – pushed to such despair that their lives were no longer worth living.

That was not true. The way the protests played out across countries, the momentum they gained across dictatorships, was not a result of an oppression that was peaking, but the relative relaxation of autocratic rule in the region. The Arab Spring protests caught fire not because dictators had people in a chokehold that had reached suffocation, but because that chokehold in the years preceding the protests had been loosened. Arab dictators had been in power for so long, the opposition parties and forces that could threaten them banned and disbanded for so long, that a complacency set in. In Egypt in particular, the host of the most dramatic Arab Spring protests, press freedoms had been increasing, and censorship decreasing, for the decade in the run-up to Hosni Mubarak’s removal. Mubarak was so certain that the protests posed no threat to him, that even as the army was plotting for his removal he was reportedly in denial that things had got serious for him.

https://twitter.com/NesrineMalik/status/1303947774996742144?s=20

But in a way life for Arabs was getting worse, but not objectively so. Political freedoms were increasing, and with them so did the means of expressing and communicating the grievances stemming from the oppression that did exist. The result was that there was a perception that things were getting worse. There was a feeling that economic circumstances, political detentions, unemployment and inequality were going up at a dramatic rate. Arab dictators’ undoing was that they were not oppressive enough.

This is the paradox that defines all epoch-ending protest, improvement hiding in plain sight, masquerading as deterioration. It’s not always the case of course, but on the whole it can be argued that all big movements that wreck the systems that went before them have capitalised somehow, in small but ultimately impactful ways, on the complacency of the ancien regime.

Subjugating vast swathes of people, be they black people, women, or political opponents requires far too many resources

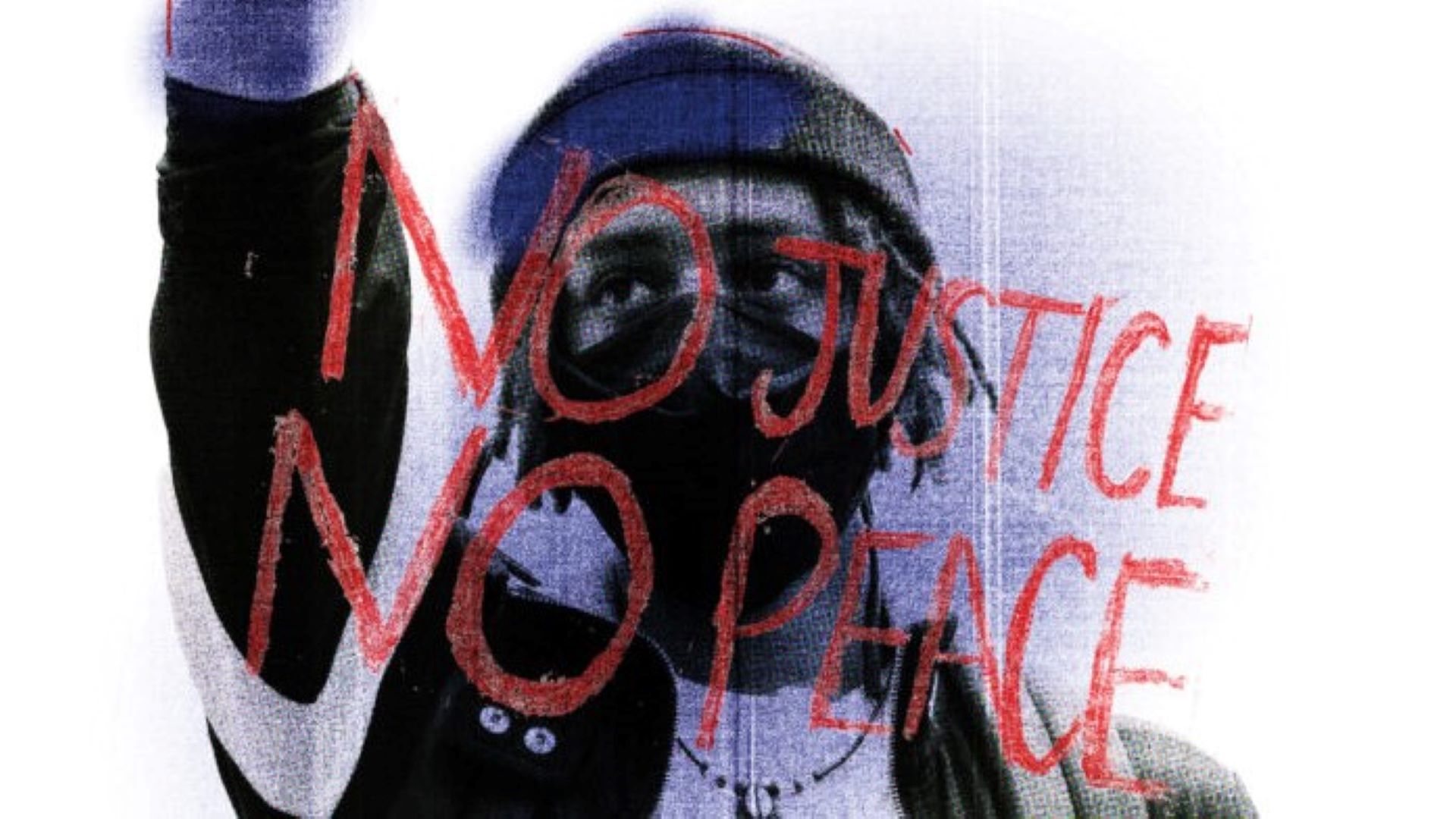

The same is happening with the summer’s Black Lives Matter movement. The way they were set off by the most emotive trigger possible, the death of a black man under the knee of a white police officer, suggested that a rising tide of discrimination against black people had finally engulfed America. The murder of George Floyd also came three years into the tenure of Donald Trump, whose presidency has given white supremacist and nationalist movements a larger clearing in the public arena. But the global movement that was inspired by the Black Lives Matter protests cannot be explained by this sense of intensifying grievance alone.