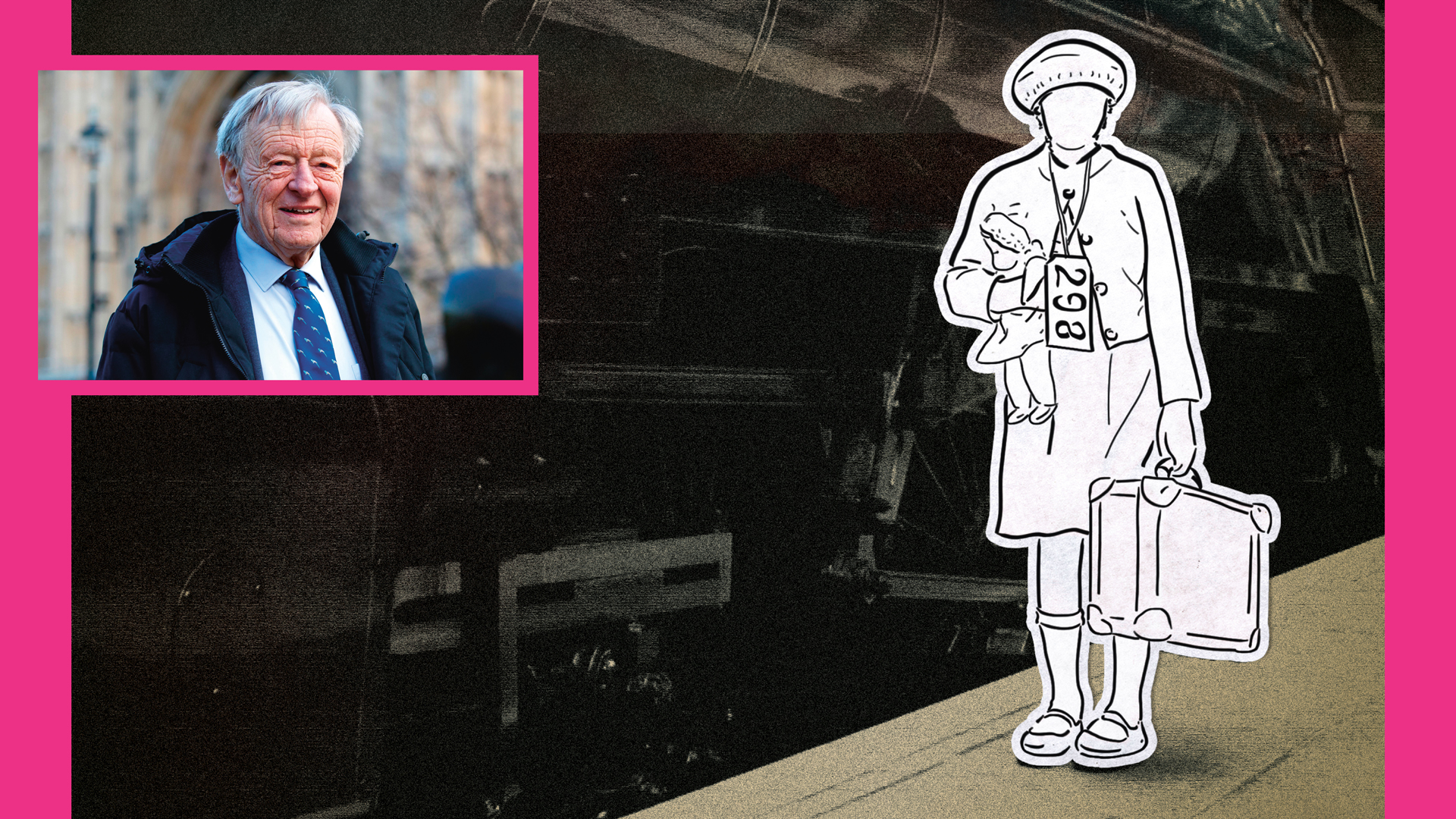

Lord Dubs first passed an amendment to the Immigration Act in April 2016 that set up the Dubs Scheme – offering a pathway to bring 3,000 lone refugee children to the UK.

Since then, the Dubs Scheme has faced a battle to continue offering safe passage to the UK with just 220 children transferred to the UK in the first two years as rows over local authority capacity and the government’s support for the scheme raged on.

Lord Dubs has been just as resolute for the EU Withdrawal Bill and refused to withdraw his amendment to protect the rights of refugee children.

Backed by charities Safe Passage and Help Refugees and a 216,000-signature petition to prevent the blocking of that avenue to sanctuary, Dubs rallied thousands of supporters at a Parliament Square protest last Monday.

This show of support was followed with a convincing defeat for the government in a House of Lords vote on the amendment, with an 80-strong majority backing the amendment and sending the bill back to the Commons.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

But the campaign ended in vain – the government held firm the following day as Conservative MPs put party politics above vulnerable children to reject the amendment with an 88-vote majority.

As the UK exits the EU this week and, poignantly, the world marks Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27, Lord Dubs tells The Big Issue why his fight to give vulnerable children a safe home and protection from traffickers and criminals must go on.

“Anyone who has visited the refugee camps in Greece or Calais cannot fail to be moved by the plight of the refugee children stranded there. There can be few sights more moving and distressing than children with no family, in a foreign country where they don’t speak the language, living in makeshift shelters, overcrowded camps or rough on the streets.

The journeys these children undertake can take years and are fraught with danger and exploitation. My journey here as an unaccompanied refugee child aged six took two days on a train from Prague and pales in comparison to the journeys being undertaken by the child refugees of today.

The painful reality for large numbers of these children is that they have been smuggled, or worse still trafficked, which means they have “earned” their way to Europe through slavery, prostitution or enforced labour. Thousands of children simply disappear en route, absorbed by criminals and their networks. Even once in the camps I have been told by doctors volunteering in Greece that the exploitation continues, and that rape is commonplace. Just this week there were angry protests outside the Moria camp on Lesbos in Greece that I visited last year with Stephen Cowan, who leads the borough where I live and has taken in some of the most desperate children. The Moria camp was built to accommodate around 2,000 people but it is estimated that there are as many as 20,000 living there now. It is the closest thing to hell on earth I have witnessed.

Some of the children in the camps or on the streets have family here in the UK, perhaps the only surviving relatives they have. Their right to be reunited with that family is enshrined in law, but that law will be scrapped when we leave the EU if the government gets its way.

As members of the EU, we are part of the Dublin Regulation, which allows unaccompanied children within the EU to apply for legal family reunion with relatives elsewhere within the EU. So, for example, a Syrian orphan who arrives in Greece hoping to find an aunt in Lowestoft has the right to apply to be reunited with her. But when we leave the EU, we will no longer be covered by the Dublin Regulation.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

This right was to have continued after Brexit, however, after my amendment to Theresa May’s Withdrawal Bill was voted on in the Lords by peers from across the parties and accepted by the government in the Commons. So, I was dismayed to discover that in the most recent incarnation of the Bill, brought just before Christmas by the current government, this right had been removed.

The Lords once again backed my latest amendment when it was debated earlier this week, and the public’s support has been overwhelming – almost a quarter of a million people have signed a petition asking for the government to restore the rights of refugee children to family reunion here. But unfortunately for the children stranded in Greece and Calais, MPs rejected my amendment.

I believe that the way we treat the most vulnerable people is a test of who we are, what kind of country we hope to live in and what humanity we have. Britain has a proud tradition of humanity and hospitality towards child refugees, myself included, so although our campaign suffered a setback this week, it is not over. The next challenge will be fought over the next few months. Children are counting on us to win it.”