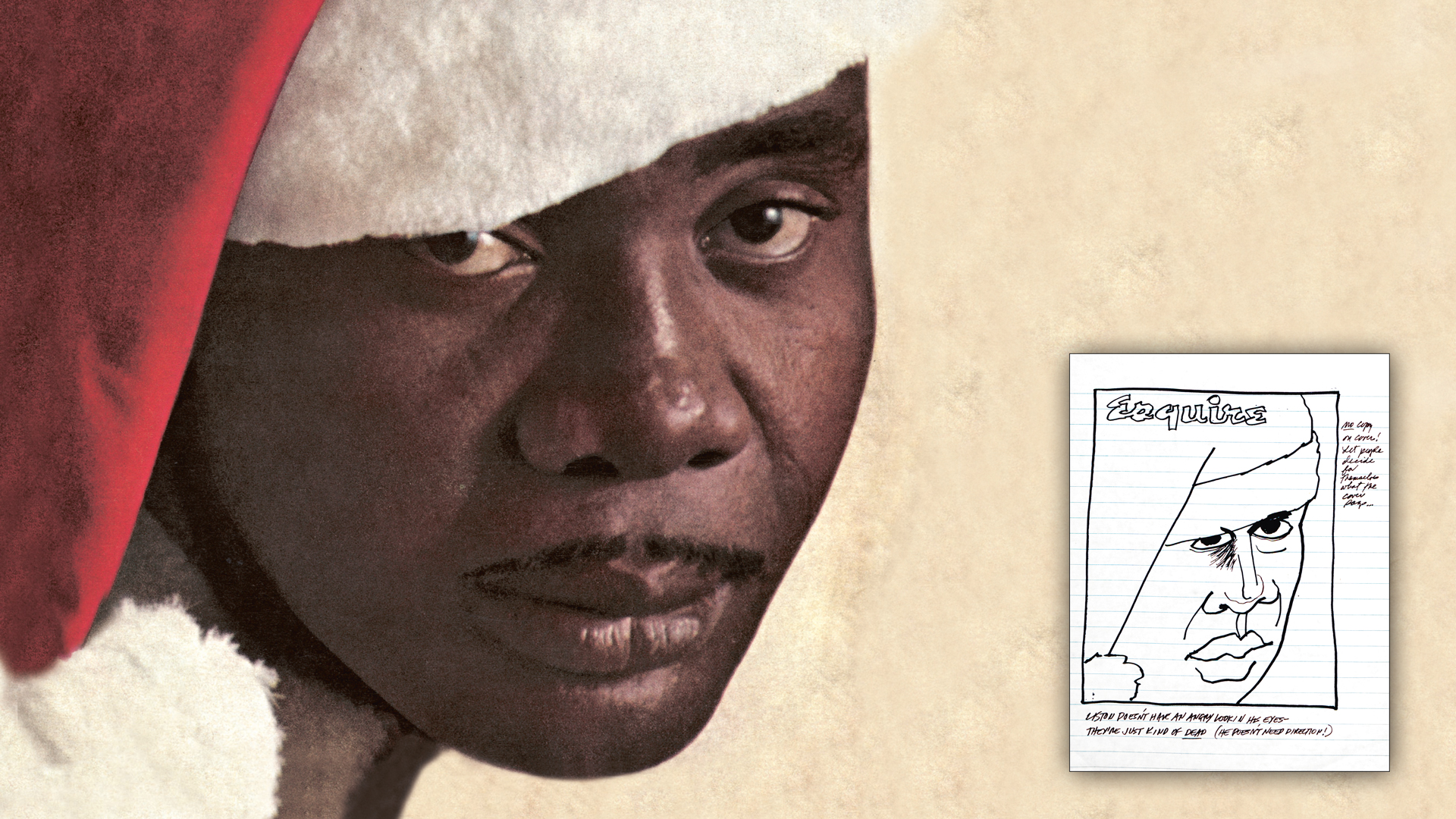

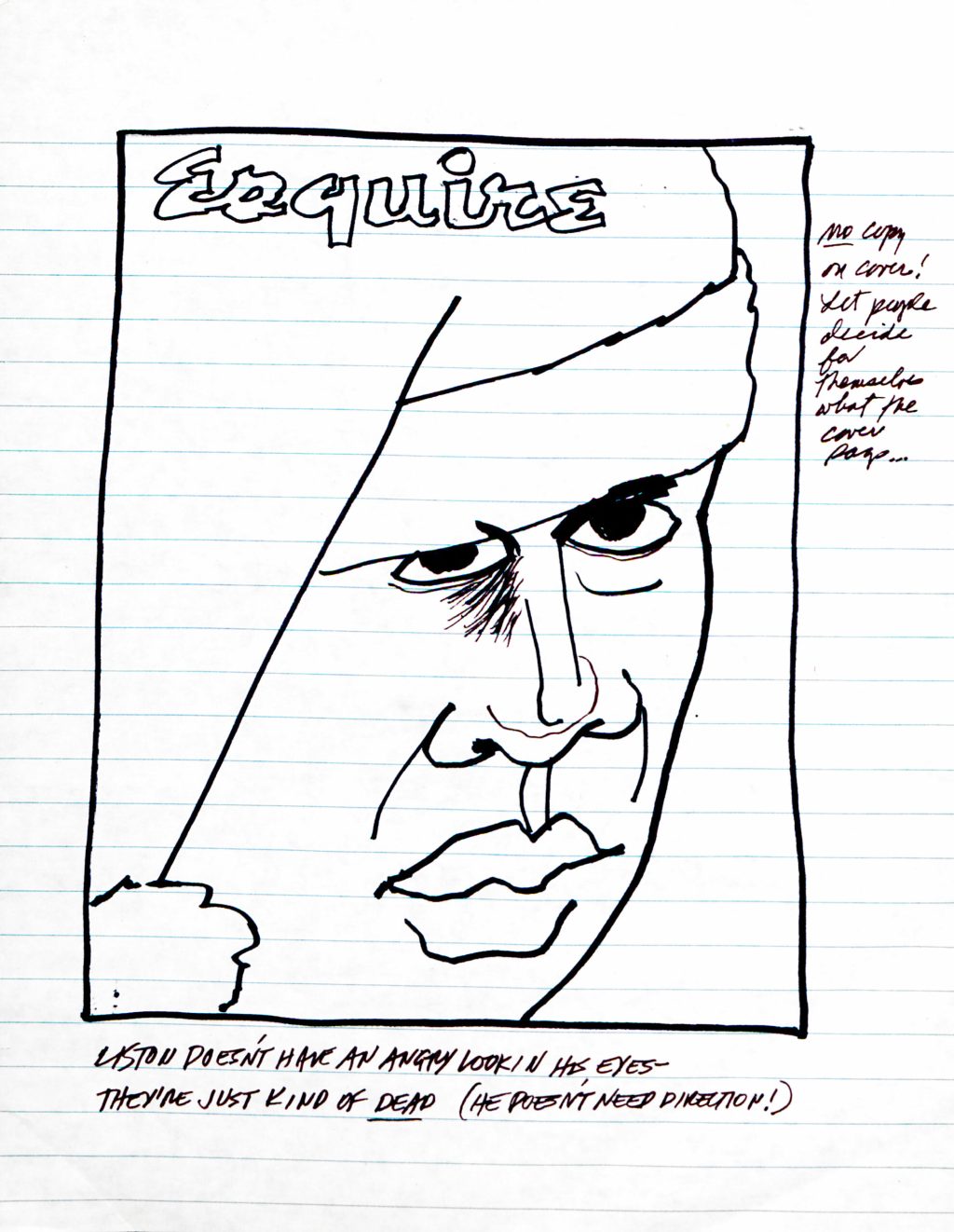

On a stifling hot day in August 1963 America’s most celebrated art director George Lois was already imagining Christmas. Esquire magazine had commissioned him to design an eye-catching and festive front cover in the run-up to a much-anticipated heavyweight boxing bout between the holder Sonny Liston and his challenger, the garrulous Cassius Marcellus Clay, who had not yet taken his Muslim name of Muhammad Ali.

Lois and his photographer Carl Fischer hired a suite at the Thunderbird Hotel in Las Vegas, where Liston trained. They lugged equipment through the lobbies and converted the hotel room into a makeshift photography studio. In a corner next to lighting boxes was a suitcase containing a carefully folded Santa costume, an elf’s hat and an acrylic white beard. Their plan was to put the most notorious boxer on the planet on Esquire‘s Christmas cover, dressed as Santa Claus. Although a celebrity playing Santa Claus is now a familiar trope of magazine journalism, the Liston cover shot was not only brazen, it came in times of heightened racial sensitivity, and what began as a creative ruse erupted into a full-blown controversy. The Liston cover not only shocked white America but simultaneously drove a wedge through the civil rights movement, many African-Americans believing that Liston was anathema to their cause.

More myths have congregated around Charles ‘Sonny’ Liston than any boxer before or since. Born in St Francis County, Arkansas on May 8 1932, he grew up in anonymous poverty, the 24th of his father’s 25 children. There was no certificate to support his birth and suspicion has persisted that he faked his age as a teenager. Whatever his real age, Liston survived a chaotic and brutal upbringing, eventually leaving home for a wayward teenage life on the streets of St Louis’s Westside. In 1950, he was convicted of first-degree robbery and spent more than two years in the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City. Prison was a turning point. A Catholic chaplain introduced him to boxing and for the first time in his life he was an achiever. His strength marked him out as a natural heavyweight and he excelled in the prison boxing programme.

On his release from prison and desperate for work, Liston befriended John Joseph Vitale, the surrogate head of the St Louis mafia. Vitale secured him a union card with the Local 110 union and found Liston a job for $25 a week working as a cement labourer. It was a front that benefitted Vitale, who could exploit Liston’s raw violence, instructing him to work as a strike-breaker and to terrorise union men that were challenging pay grades in the concrete industry. From there, Liston became a debt collector for the mob. To the loose talkers in the world of boxing, his work in the cement industry and his nefarious bosses provoked speculation that he disposed of bodies and had littered the concrete bridges of America’s expanding highway system with the dead or dying. It was almost certainly an exaggeration but in boxing myths multiply, and Liston’s associations with murderous crime enhanced his reputation as a stone-cold killer.

By Christmas 1963, racial tension was America’s raw nerve. The civil rights movement backed Liston’s more trustworthy rival Floyd Patterson and even President Kennedy confessed that it would be a reversal for civil rights if Liston reigned as heavyweight champion. The writer LeRoi Jones, later to become Amiri Baraka, believed it was all racial stereotyping and that Liston had become “the big black negro in every white man’s hallway, waiting to do him in, deal him under, for all the hurts white men have been able to inflict on his world”.

Into this exaggerated melodrama came Cassius Clay, who personified a new generation of African-Americans. Black journalist Alex Poinsett was the first to detect a more complex side to Clay and to the racial dynamics of boxing. “When he says ‘I am The Greatest’, he is not just thinking about boxing…” Poinsett wrote knowingly.