I recently explored Ireland’s border from end-to-end. I wanted to get to know the border’s true character, to meet it on the ground. I also wanted to learn more about its past and what it might become in the future.

The Brexit vote brought much anxiety to the borderland, worries about how the United Kingdom’s only land frontier with the European Union would operate. A hard border, with mandatory stops for customs, would not just be bad for business but could threaten the peace process.

In 1993, when both the Republic of Ireland and the UK joined the single market, customs checks were no longer necessary

The anxiety was exacerbated by Downing Street’s refusal to commit to anything, apart from leaving the single market and the customs union. The European Council are no less intransigent but they are much more open about what they want from the divorce. Just over a week ago their operating guidelines were published and Ireland’s border was given emphasis: “In view of the unique circumstances on the island of Ireland, flexible and imaginative solutions will be required, including with the aim of avoiding a hard border.” Days later, the EU’s chief negotiator Michel Barnier said he would “pay particular attention to Ireland”.

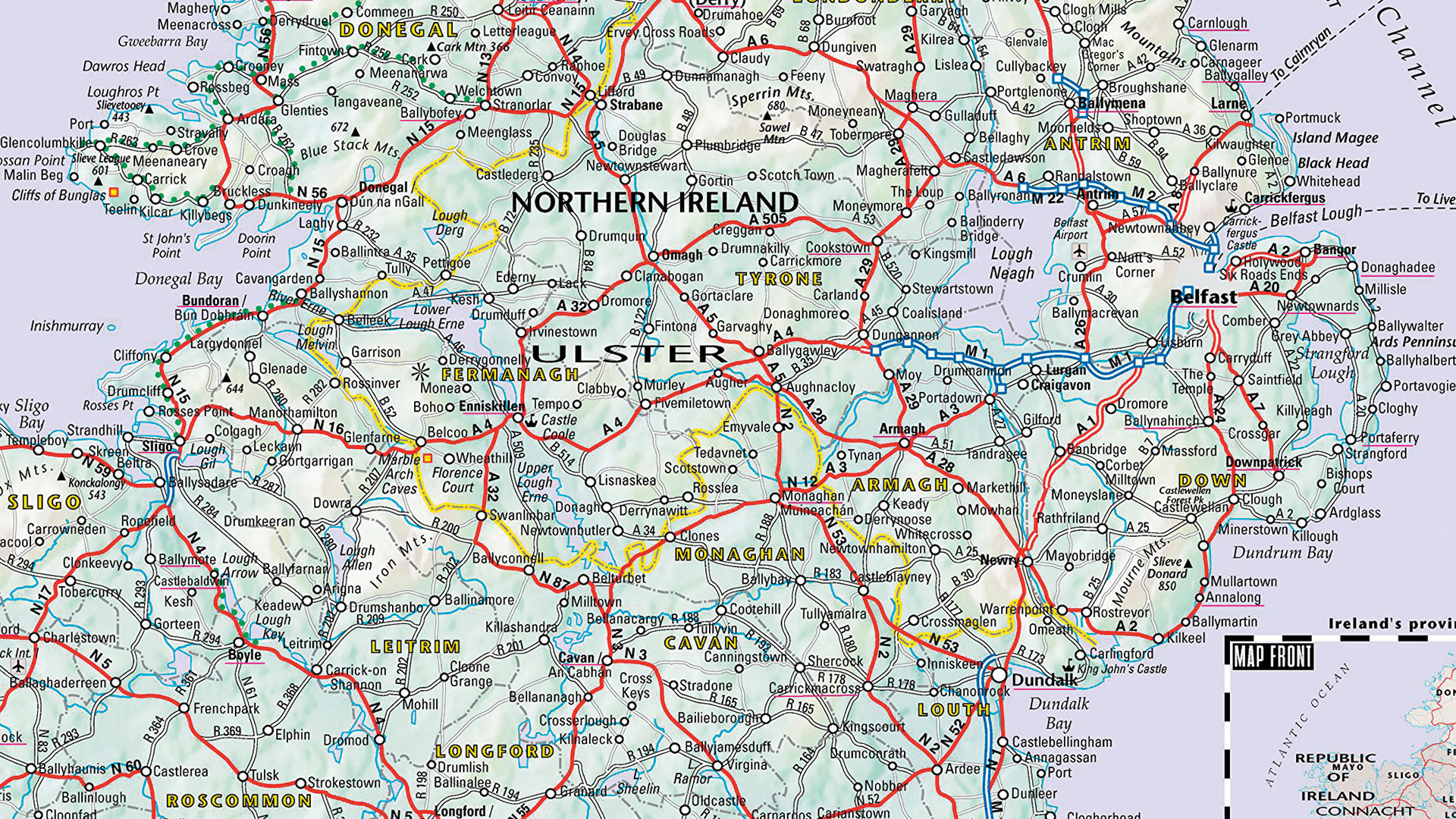

On the ground, the first thing you notice about Ireland’s border is that you can’t see it. In 1993, when both the Republic of Ireland and the UK joined the single market, customs checks were no longer necessary. That layer of bureaucracy – manifested on the border by queues of traffic and customs facilities – disappeared. Then in 1998 the Good Friday Agreement set in motion the process of dismantling military installations along the frontier.

Nowadays you must look for more subtle indications to locate the border, such as changes in the road surface or carriageway markings turning from yellow to white. Away from the roads there is even less to go by. The border corridor is almost entirely rural, fields and forests, although the invisible line is always hosted by something; a fence, an old stone wall, a hedgerow or, most commonly of all, a river. The most frequent sound along the border is trickling water, along with the coo of wood pigeons and puttering of tractor engines.

A common smell is the tang of diesel. One bright cold morning I was walking a narrow border lane in Armagh when I experienced this smell again. It was coming from a cube-shaped plastic tank sitting on a layby. It was about four feet tall and semi-transparent so I could see it was half-full of sludge that had settled into two layers. Liquid the colour of varnish was floating on top of something black and tar-like. Both layers looked poisonous. I walked around the tank a few times, wondering if it was what I thought it was. Whoever left the tank had wedged a couple of planks underneath to stop it tipping over. You could call this gesture considerate and it made me wonder if the tank was left for an official waste disposal scheme. This was too optimistic, as I found out when, a few minutes after me, a local council employee arrived in a car. “No, no, it’s just been dumped here,” she said. “We get a lot of them.” She took a photograph of it. I later learned some of this waste material is shipped to Holland to be disposed of properly. Having recorded the location of the illegal dump she drove off. Her electric car was a pleasing contrast to the toxic atmosphere around the tank.