So why did two privately educated white males in their late sixties feel the need to write a book about the issue of private schools in Britain? Partly because of a nagging sense of unease, about how whatever we have managed to achieve in our lives has owed at least something to a wholly undeserved head start denied to the great majority of our contemporaries. Partly because of our awareness as parents in the state sector of the almost grotesquely unlevel playing field, with one of us also having been a governor in state schools as well as a volunteer with children’s sports clubs. And partly because in our professional lives – one as an economist, the other as a historian – we have been increasingly immersed in the profound damage that the entrenched educational apartheid has done to modern Britain.

Yet all that said, probably the single greatest driving force has been a deep sense of frustration. On any objective and dispassionate reading, whatever one’s particular stance, the issue of private education is clearly an important one. Perhaps less so in other countries, where private schools are not nearly as closely linked to the centres of political power, but undeniably so here. Yet, astonishingly, our politicians and policy-shapers very seldom mention the issue, let alone offer a way forward. Among current leading politicians, only Michael Gove and Andrew Adonis have been willing to put their heads above the parapet and say something of real substance.

We include in our book a Guardian cartoon from July 25 1968 depicting a cross-looking man writing a letter to the editor: “Sir, with reference to your leader on the public school system’s divisive influence on our society…” On the wall above him is a calendar with the date: July 25 2068. We are now nearer to that date than we are to 1968. And in case any younger readers are puzzled about the terminology, we should explain that private, fee-paying schools used – for reasons lost in the mists of time – to be called, ludicrously enough, “public” schools. That at least has changed for the better, though the schools themselves prefer the more feelgood “independent”.

At heart it’s a problem of unfairness,

So what’s the problem? Why do we need to do something about what are after all often excellent schools? At heart it’s a problem of unfairness – an unfairness that, both substantively and symbolically, undermines all notions of a cohesive and equitable society, as well as a society in which talent and hard work, as opposed to the circumstances of birth, determine life chances. Consider these two fundamental facts: one in 16 children go to private schools; but one in six teachers teach at private schools.

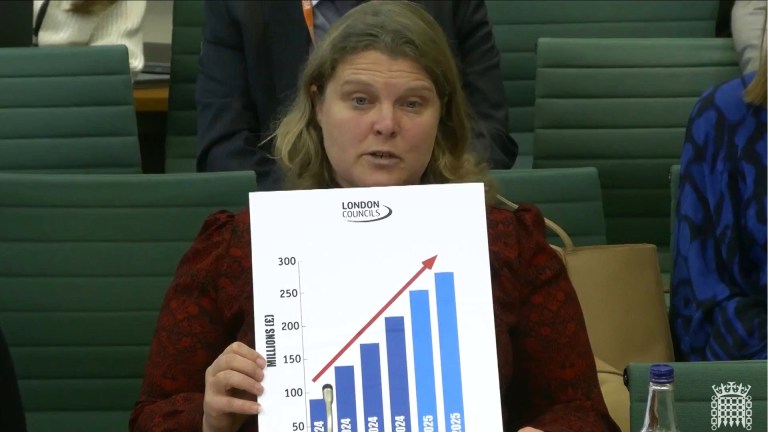

Given which, it is unsurprising to learn that the day-to-day resources gap between the private and the state sectors is roughly three to one. Much smaller class sizes, lavish facilities, an eye-catching range of extra-curricular activities, the intensive cultivation of ‘character’ and ‘confidence’, the high and thus exclusive price tag (fees up threefold in real terms since the early 1980s) sustaining a concentrated peer group of children mainly drawn from supportive and affluent families, highly resourced and knowledgeable, ‘working the system’ to achieve the best possible exam results and the highest rate of admission to the top universities – all these elements mean that the private sector is by and large operating in a parallel universe to the impoverished and often demoralised state sector.

With these privileges of money, the privately educated enjoy an almost unimpeded path from school to top university to prestigious, high-paying career; the block on social mobility is not only in an upward direction (earlier this decade the Prime Minister, the London Mayor and the Archbishop of Canterbury had all gone to the same school, which was not Windsor Comprehensive), but also downward (with all those nice-but-dims still getting their places at Russell Group universities), which is crucial given that for social mobility to work properly it has to be a two-way process; and with so many of our national leaders – not just in politics, but also the media, law, business and much else – being drawn from a privately educated elite, inevitably with little instinctive understanding of what life is like for most people, there is in effect a serious democratic deficit.