I want to write something funny, but what’s funny about this moment? We’re all being urged to give freely of our services, but while others offer hair-cutting tips and online baptisms, the best I’ve got to offer are gags. Do people really want gags from someone like me who’s running low on good cheer? I’ve always been an optimist, but while a shard of it remains, I’ve never had that optimism more tested and shat on than now. Now makes us yearn for the happier pre-Covid days of Brexit, the rise of totalitarianism, koalas on fire, and the total control of our lives by Mark Zuckerberg and the government of China. Now, we’ve turned our living rooms into an open prison while outside the police are on the point of Tasering sunbathers.

The common moment of quiet confidence in the face of medical officers’ advice has gone. We’re at that point where passengers on turbulent flights realise the reassuring tone of voice pilots use when they say, “It’s going to be a little bumpy for the next couple of minutes,” is the same one they use for, “We’re about to crash into a mountain.” It’s the tone of voice we detect coming from increasingly nervous ministers saying the Prime Minister is doing “just fine”. The looks on their faces are less those of confident decision-makers, and more the look I imagine a sparrow would have if it was clearly explained to him that he’s now running the country. Much of my career has been spent writing comedy about how people who sound like they know what they’re talking about don’t necessarily know what they’re talking about. I’m not sure if I dressed that message up in punchlines now that it would help people pull through.

My creative dilemma isn’t worth a macaque’s anus set against the daily trauma being faced by millions across the country

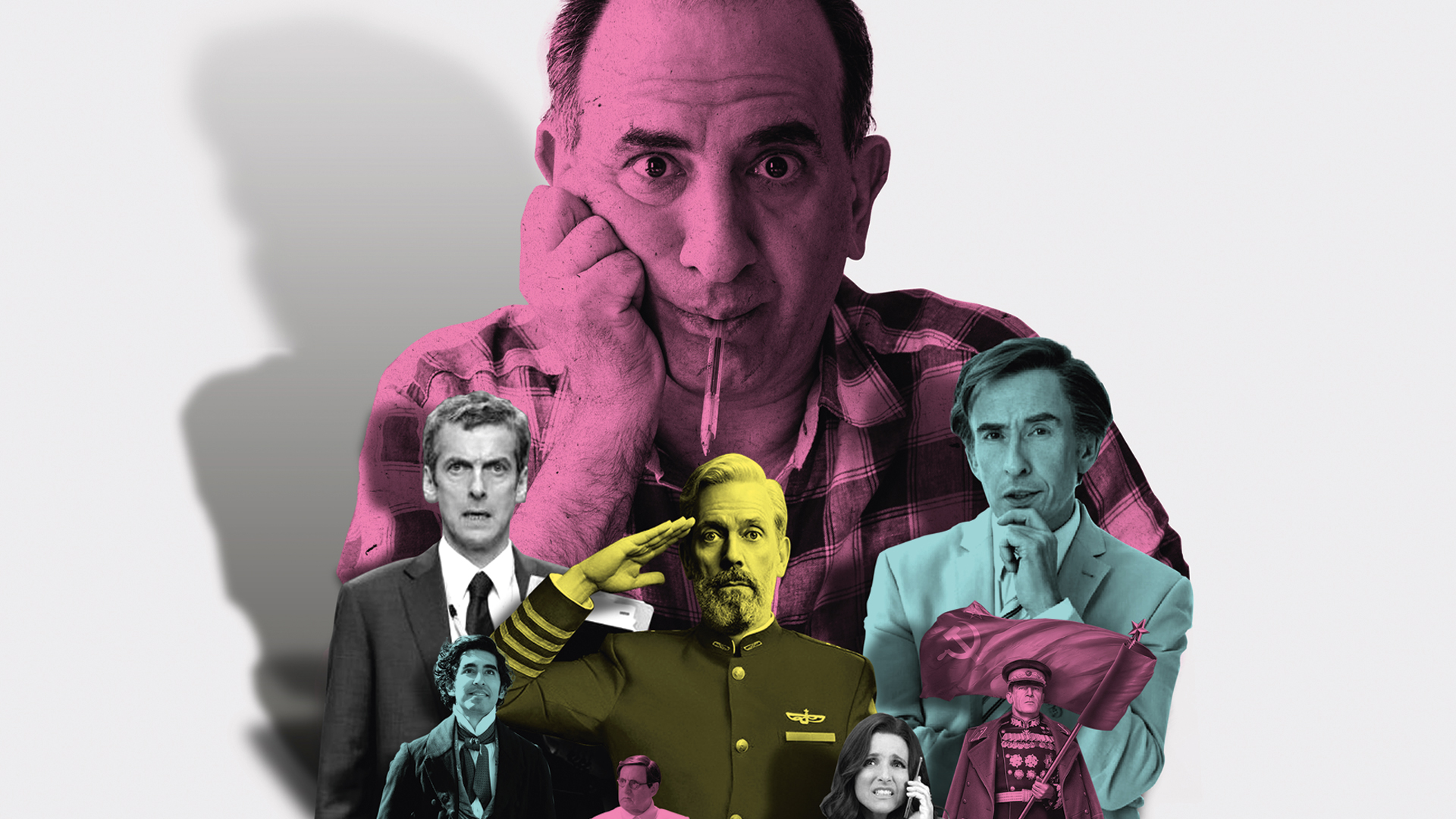

I used to be more positive. When businesses all around me began seizing up I felt enormously thankful my work was something I could easily do from home and for which I’d always assumed there’d be a terrific demand. Then I Iooked at the work I was doing. I’m in the middle of getting scripts ready for the second season of Avenue 5, my show for HBO and Sky. It’s set in the future and involves six-and-a-half thousand people on an eight-week space cruise around Saturn suddenly finding out, because of a glitch, they’re going to be stuck there for eight years. The first season went out just as cruise liners in the present day became floating pandemics. Now, looking ahead to what we’re planning for season two – a chaotic fight for survival led by a broken leadership among dwindling supplies – I’m wondering whether people are ready for jokes about death lotteries.

Still, it’s work, and I should be grateful. My creative dilemma isn’t worth a macaque’s anus set against the daily trauma being faced by millions across the country: worries about rent, a rise in domestic abuse, relatives dying alone, businesses going under, work drying up, anxiety turning toxic, education fragmented, dreams all abandoned. Sadly, this moment is more profoundly funny-peculiar than funny-ha-ha.

Most peculiar of all is this induced coma we’re living in at present, an enforced hibernation whose end-point is hope but whose reality is helpless detachment. Most of us try turning our bubbles of isolation into something positive and active: binge-watching Gomorrah, learning Portuguese, getting out the telescope, posting videos of our family singing funny songs about how youths who congregate in parks have blood on their hands to the tune of The Laughing Policeman. We pretend to each other, and know we’re pretending, that this is like some extended and much-needed family break from a hyperactive life, a chance to slow down and find ourselves. And so what if we’re stuck indoors for a long time: I’ve had holidays in Devon like that. And at least we get the chance to step outside every Thursday night and bang a pot with a spoon. I could write jokes for that sort of time.

What I do know is that this future will be coloured by our experiences of this extended now

But, no, this is no holiday. Of course it isn’t. Instead, each of us sits in a strange and prolonged silence at the epicentre of a not-so-distant scream. Leisure time has been forced upon us, but because of a hundred thousand tragedies we can’t stop. Many commentators have observed in their more lyrical moments that, to quote TS Eliot, we’re at a still point in a turning world. If that’s the case, then the turning is getting louder and louder. Websites and supplements may still project a cheery pattern of family discovery, the friends we can call, and the games we can play; but we can also hear the ambulances. We worry about an elderly parent, we offer sympathies for their loss to someone we know, and we quietly fret every day about those close to us with underlying conditions. We act in holiday mode because that’s what is being asked of us. It’s our duty to bloody well remain calm until it hurts.