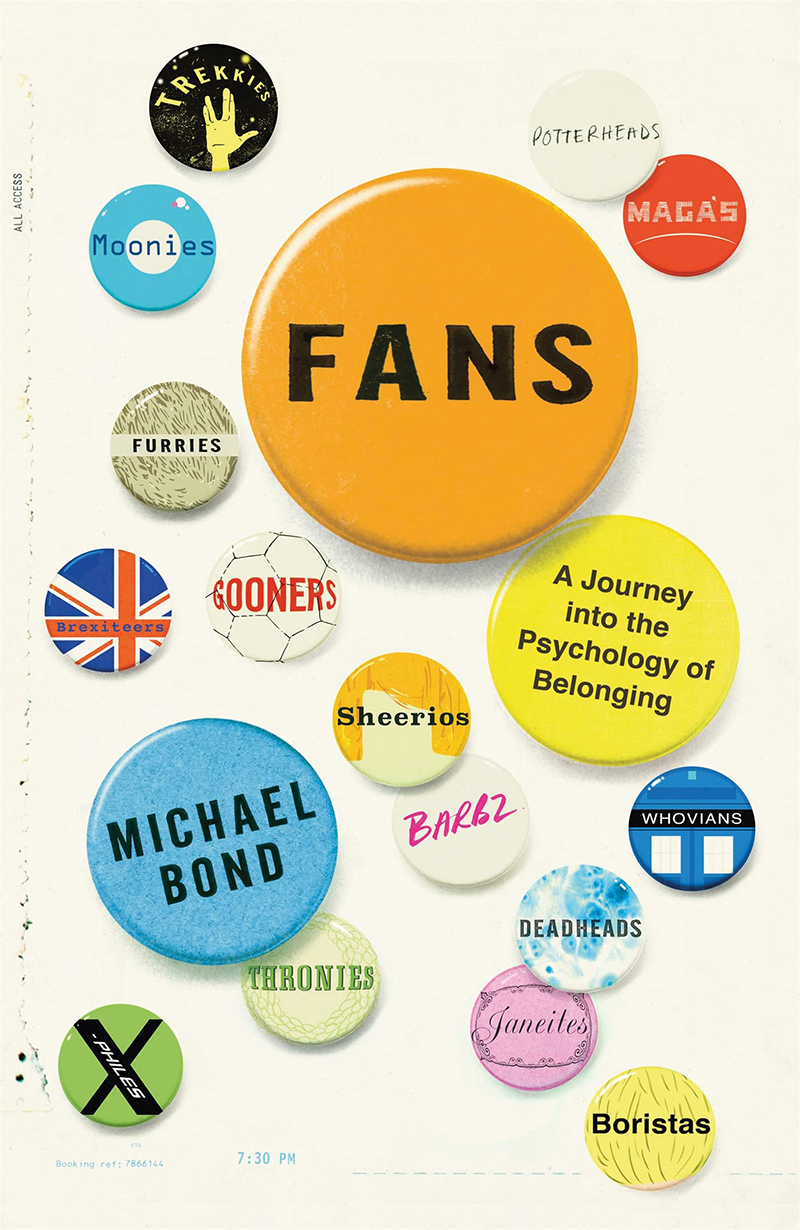

What comes to mind when we think of fans or fandom? Pop-loving teenagers screaming at a Harry Styles concert, perhaps, or the ‘Swifties’ who live their lives through the songs of Taylor Swift. Or the thousands of people who still make a living impersonating Elvis Presley. We might imagine Trekkies, Potterheads and Thronies in their fictional universes, or the zeal and passion of sports fans – with a special thought for the basketball enthusiast who paid $1.5 million (roughly £1.2m) for Michael Jordan’s trainers.

Fandoms such as these, which celebrate the most visible elements of popular culture, attract a lot of attention, but they are not the only game in town. Every cultural phenomenon has its devoted followers; they exist in places you would never think of looking. Some of Jane Austen’s most ardent fans are twenty-something feminists. Richard III, the ‘Hunchback King’ who supposedly killed his nephews in the Tower, is today defended by several thousand Ricardians who believe history has been unkind to him. They are no less fan-like in their loyalties than Swifties and Harries.

Your support changes lives. Find out how you can help us help more people by signing up for a subscription

Recently, fan sensibilities have migrated into politics. This may sound surprising, but fans have always shown a dogged and sometimes irrational allegiance to their tribe, a trait that has become endemic in party politics. The relationship between political leaders and their supporters in many cases resembles the relationship between celebrities and their fan groups, where the leader is symbolic of the group’s identity. The increasing polarisation in politics has created fertile ground for those who favour performance and personality over policy. This is why, in addition to Trekkies, Potterheads and Thronies, we now have MAGAs (fans of Donald Trump), Corbynistas (Jeremy Corbyn) and Boristas (Boris Johnson).

The rise of fan dynamics in politics has been greatly assisted by social media, which enables people with common interests to participate and cooperate on a scale that has not been possible before. Social media also partly explains the growth of so-called ‘dark fandoms’ in which people come together to share their fascination for true crime. This enchantment with the macabre was visible earlier this year following the disappearance of Nicola Bulley while walking her dog by the River Wyre in Lancashire. In the three weeks before police retrieved her body, hundreds of people descended on the area to hunt for clues, take selfies on the bench where she was last seen and stalk the people they suspected of abducting her. Many more offered their theories online.

- Benedict Cumberbatch: Filming in front of the ‘superfans’ is quite special

- Donald Trump and the hate groups he emboldens

- How social media has changed our world

This spectacle was unedifying and worrying, but it was nothing new. True crime fandoms go back far beyond celebrity culture. Consider the events in Plainfield, Wisconsin, during the winter of 1957-8. Over several months, tens of thousands of Americans visited the town to peer at the home of Ed Gein, a reclusive bachelor who had recently been arrested for killing two women and digging up the corpses of several more. Police had discovered a gallery of monstrosities in his house: the headless, disemboweled body of a local shop owner hanging by her heels in the kitchen; a collection of female genitalia in an old shoebox; human skulls repurposed as soup bowls.