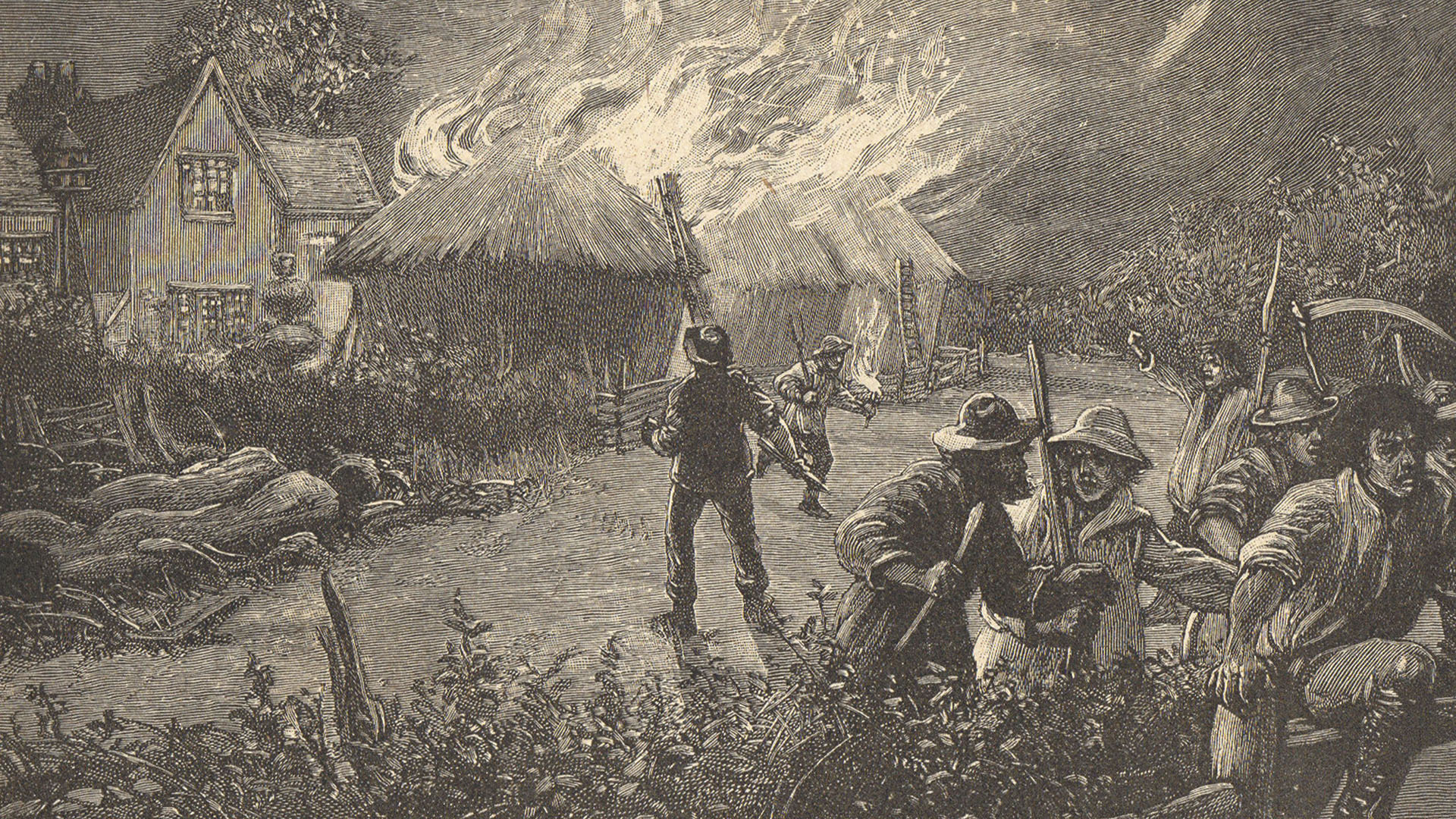

“Circa 300 years ago in Britain, we had an agricultural revolution that created the first machines for planting and bringing in the harvest. Modernisation of farming led to the need for fewer workers on the farm and this led to many more people drifting around hungry and broke and unemployed. At about the same time, to encourage the growth of farming and wealth into the hands of the better classes, they enclosed the common lands through acts of parliament so that poor peasants could not graze their animals, or collect firewood, or catch rabbits for their evening meal.

So these two things led to death and dislocation and more people going off to the colonies, and then after the agricultural revolution came the big industrial revolution which mopped up many of the loose and lost peasants who had been driven from their lands. I am sure some conservative historians will dispute this flow-of-people theory, but I’m sticking to it.

“So the peasantry was virtually destroyed in the countryside, or reduced to such small numbers that you could say that England in particular became a virtually peasant-free country. All those native skills of knowing trees and how to repair a headache with berries off bushes, and all that wisdom about the natural world, went up in smoke. And was replaced by the new skills of hopping in and out of machines without having your head or your arm cut off, and living on bread and cheap beer, and being able to sleep in a corner of a hovel with many others and drink yourself into oblivion of an evening time, and being generally wretched; all this about the time that Jane Austen was writing about philistines in their drawing rooms with their voluminous skirts worn over half a dozen petticoats.

“And rich people could speculate on distant plantations that used the slave labour of captured and tortured Africans to grow sugar for the ever-sweet tooth of the increasingly wealthy middle and upper classes who got their head start in the agricultural and industrial revolutions and could therefore rush headlong towards becoming (imitation) aristocrats and have dozens of handkerchiefs and drawers stuffed full of silk raiments. And join that whole ugly, poncified, self-denying life of the British comfortable classes.

“And then have that big and burgeoning and murderous life-shortening Victorian British Empire and the continuing worsening of the body and minds of the poorest working among us. The crudification of human life to being obsessed at one end with the appearance of wealth and the frippery of plenty, or at the other with feeding your children and yourself from the paucity of the money handed to you for wearing yourself out in the course of the working day and night.

“The British Isles became largely a crude cauldron stuffed full of mental and physical health problems; and down through the generations the population and the alienation increased until two world wars were added to this, along with the collapse – a bitter collapse – of the industrial empire, with people left wretched within the shells of a failed economy and society. Out of which grew a psychosis of such magnitude that all the kindly liberal people couldn’t put Humpty together again.

“In the meantime, Finland grew to be a major economy in northern Europe that never had an industrial empire, or a territorial murdering empire, and had not exploited half the world and made its people sick of worry as to how to wring the next decent wage out of the bourgeoisie.

“It might be slightly different cleansing the streets of downtown Helsinki of homeless people – Helsinki, capital of Finland, with its mindset not formed from hundreds of years of self-inflicted suffering. Don’t you think?” I asked the astonished think-tanker, who looked at me as if I had turned on a lunatic button in my head. I shook the geezer’s hand and said, “Perhaps the next time you are contemplating the similarity between chalk and cheese, you might note there isn’t any.”

Our indefatigable fight to rid the world of poverty and its attendant homelessnesses must not pause for another moment, I thought, as the man negotiated the homeless people on the corner looking for an answer to the biggest problem in their lives: how to get inside for the night.

Such is September in Westminster.

John Bird is the founder and editor in chief of The Big Issue. Read more of his words here.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? We want to hear from you. Get in touch and tell us more