As I write this, it is the day before the St Martin-in-the-Fields annual service for commemoration of people who have died in our community. This is one of the most important days of the year for our homeless community in London. The church, which holds about 500 people in the nave, will be packed. Both Choir with No Name and Streetwise Opera will sing and the Gavin Bryars ensemble will perform the iconic Jesus Blood Never Failed me Yet. Community members and workers will participate in the service and do the readings. Most importantly, we will read out the names of our dead.

The names will be read by people with past experience of homelessness, people who are still homeless and people who work in homelessness. The way that Revd Richard Carter, associate vicar who leads the service puts it is ‘people who have known homelessness’. We will come together to honour our dead. In reading each name, we hold the person up with all 500 people there. In reading each name we affirm that individual was loved and that they mattered.

As Gary Birdsall who is one of the list readers for 2024 puts it: “It’s remembering as I call it comrades or friends who have been out there – slept out, been through it, been in the homelessness situation. We’re just remembering them.”

Death scholars identify three types of grief ritual evident in all cultures. Honouring, letting go and self-transformation. When someone dies, we need ritual to grieve effectively. We need to be able to touch on the sacred – or liminal – with some kind of service or process of collective remembrance that makes sense for the culture of the deceased. We also need to transfer some of the grief into a physical object, this purpose is often fulfilled by having access to the person’s ashes or physical belongings. These rituals are global to all human cultures. In homelessness however, they are often prevented from happening. This multiplies and deepens our grief when we lose a community member – making healing almost impossible. When a member of our community dies, often we do not know, we are not informed and we are not invited to the funeral. This is usually due to a fragmented and excluding system in which the concept of GDPR is invoked (incorrectly) to create an unnecessary barrier between blood family and street family. This means that street family cannot grieve and blood family cannot hear how much the person was loved.

In Museum of Homelessness, we have become inadvertent specialists in death. Since 2019, we have run the Dying Homeless Project which aims to document and honour everyone who dies homeless in the UK. This includes a national investigation, the centrepiece of which is an annual count, an online memorial, an annual vigil outside Downing Street and holding year-round grief spaces online and in person. On rare occasions, we have been able to overcome unnecessary red tape and bring street family and blood family together for collective remembering. These are beautiful spaces where complicated grief around homelessness which often can include anger shame and guilt can be processed.

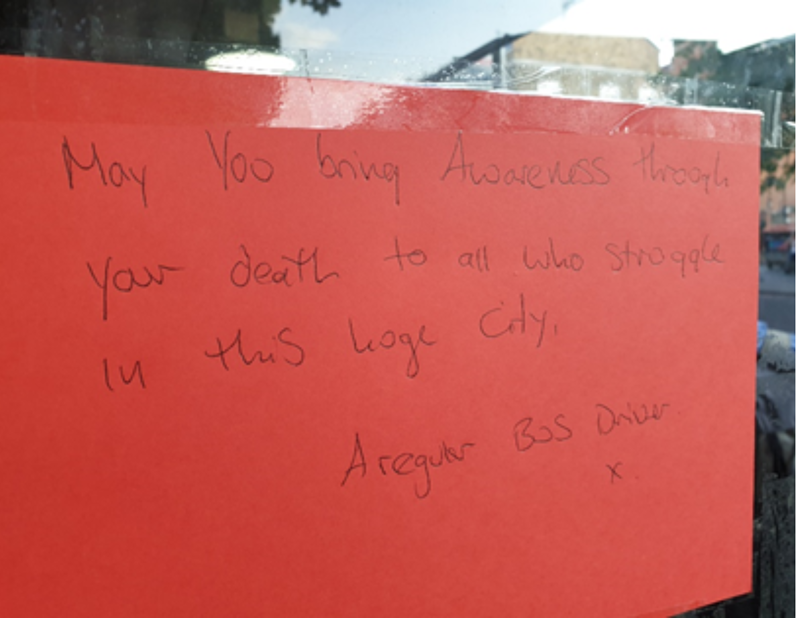

This is essential, especially for trauma survivors who are already holding so much unprocessed emotion when a friend dies. Yet the spaces, objects and rituals in homelessness where people can be grieved are few and far between. People make their own. This is evident in our Dying Homeless Project research where impromptu memorials spring up to remember people. Sparky’s bench in Regent’s Park, with an unsanctioned bronze memorial label superglued on, A shrine to Paddy in Queen’s Street, Cardiff, 100 people gathering at a bus stop to remember Musa Sevimli with one bus driver stopping in rush hour traffic to write: “May you bring awareness through your death to all who struggle in this huge city, signed, a bus driver.”