The current housing crisis began more than 100 years ago in the First World War. In order to put a stop to the continuing increase in rental levels faced by returning soldiers, an increase that had begun almost as soon as war commenced, the government imposed a control on rents. And that control continued in some form or other until the Conservative Party’s Rent Act of 1957.

Between the rent controls of the First World War years and 1957, rents stayed low. The 1957 Act brought in a novelty: once the property was vacated, a new market rent could be imposed on the new tenant. This opened up the working-class housing market to changes that had not happened for almost half a century.

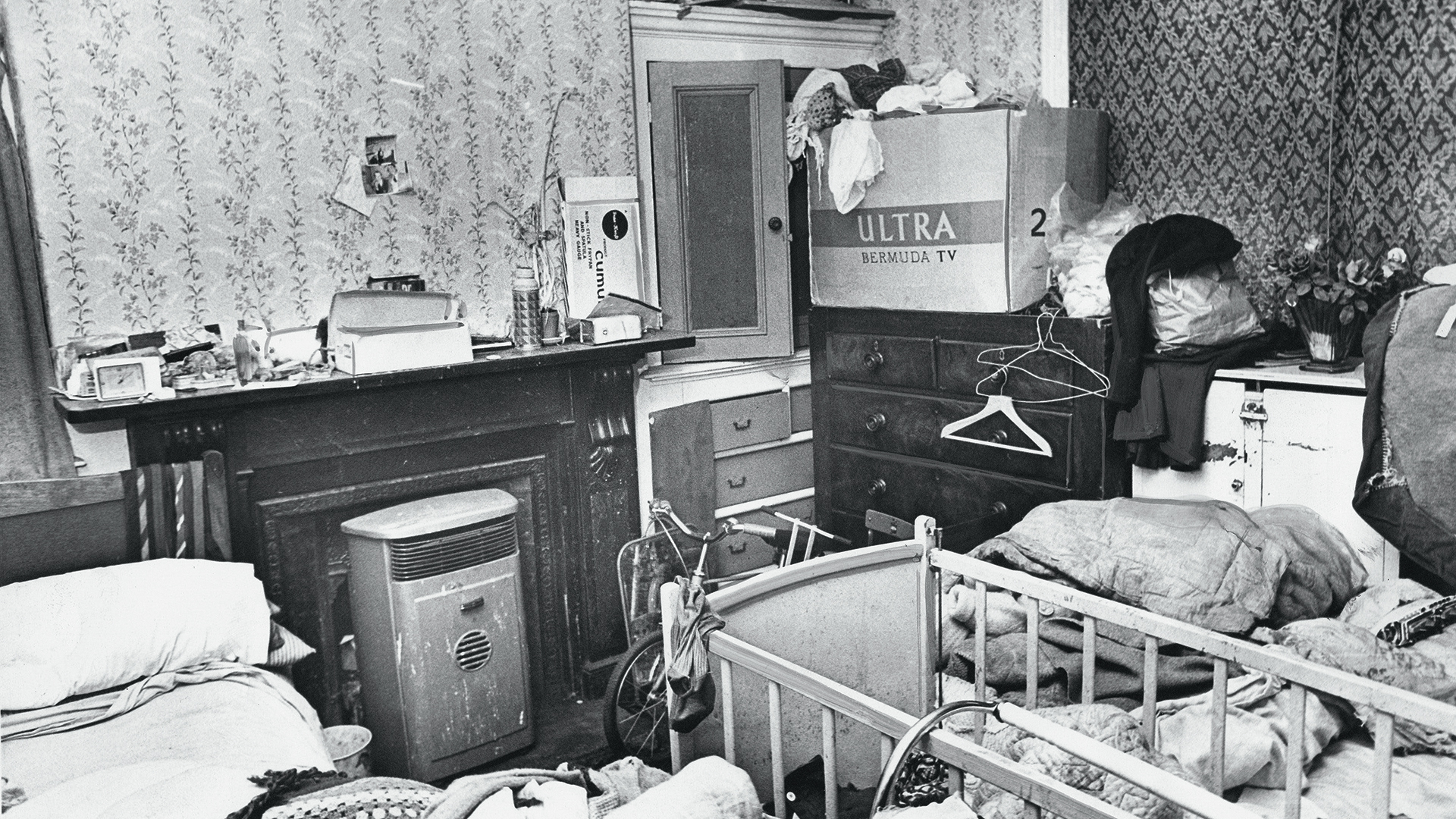

With rents artificially low as inflation increased gradually through the decades, landlords failed to address repairs and improvements. After the Second World War, 90% of working-class housing – representing three-quarters of the population – was sub-standard. The keeping down of rents had taken value out of property owning, so landlords were not investing their income in repairs.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

The 1957 Act led to landlords like Peter Rachman starting to drive tenants out by removing front doors or filling rooms with West Indians (this is in Notting Hill). Rachman claimed he was providing for the Windrush generation, but did so by dislodging white locals from their cheap, run-down flats and charging higher rents to these new tenants. Slum landlordism contributed to an appetite developing in the Labour Party – who were in opposition – to do something about this new displacement of tenants by unscrupulous means.

Labour came into power in 1964 and their 1965 Rent Act introduced rent tribunals. This meant any person could refuse to pay rent until a tribunal had decided a fair rent, which sent shockwaves through the landlords’ world and resulted in the removal of much housing from the rented sector. Landlords started to sell the at-times ridiculously cheap properties largely to middle-class people, who suddenly found the opportunity of living in houses they could gradually redevelop into valuable properties, creating a bigger, in fact a vast, so-called property-owning democracy. The gentrification process came into being.