Stewart was a photographer in his native Kingston for the Jamaica Gleaner. He was obsessed with photography and would often buy cameras with his meagre salary as a train cleaner, or later as a plastics machinist in North Kensington’s Latimer Road. He would run out of money and often sell me an odd camera to make ends meet.

He was the first photographer I knew. He took a delight in small cameras and when I built a dark room by Paddington Station he would spend his two weeks holiday working there through the night, developing and experimenting. He did an odd wedding, and even funeral, but was never able to make his mark with photos after he got off the Windrush in 1962.

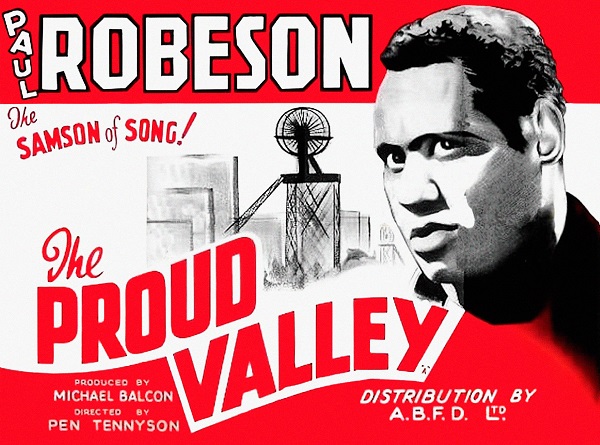

He died of cancer 10 years after I met him, in South Wales where he was a popular man because he was big and black and reminded them of Paul Robeson. Robeson had made a film (The Proud Valley, 1940) about the mines, among the miners. Stewart died in love there, after having lived almost 20 years without it. He was gentle and incredibly educated, always correcting the at times poor grammar to be found in the revolutionary paper we both sold around pubs in Shepherd’s Bush and Hammersmith Broadway.

On occasions as we went around selling I would goad him into anger, a bit like baiting a large bear, and had on odd occasions to run for my life. After such baiting I would have to be careful when I next knocked on the window of his ground floor room in Shepherd’s Bush. But overall we valued and appreciated each other. He was fascinated by my stories about growing up as a slum boy hater of blacks and Jews, and would have me tell him the story countless times of my instant conversion when I became a Marxist in Paris in 1967.

When we talked about racialism, as racism was then called, he always said roughly the same thing. “In 1945 your middle and upper class government invited the poor of other countries in the empire to join the poor of Great Britain. They did not invite the poor of Jamaica for instance to join them in Mayfair and Hampstead, nor into their Oxford country cottages, but to join the poor in Brixton, Notting Hill and other poor parts of the British cities.”

Stewart in many ways has become more important for me with the passage of time and tidesJohn Bird

Once, walking through Hyde Park on our way to a demonstration, he said memorably, “They said ‘come to our white lands. Come and sweat and labour and be poor with our white poor’.” Stewart – as we called him, as he only announced his first name when almost dying – was incensed at the lack of education and preparation for such an enormous change to the lives of poor white people. “No wonder there is racialism in this white land. Imagine what it would be like if thousands of white people tried to move into Trenchtown in Kingston, Jamaica! Murder! Mayhem.”