The Cast Courts at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum are like a greedy grabbing-up of some of the most important sculptures and pieces of architecture in the world. But in fact it’s not a grabbing-up. Because the great array of artworks are plaster-cast copies of the real thing. It’s a hoard of big bits of the works of – among others – Michelangelo. If you can’t get to Florence to see the giant David standing in the Galleria dell’Accademia, pop along to the V&A and you’ll not be disappointed by the vast replica, looking like the real thing.

I went to the V&A last weekend because I wanted to look again at a place that meant so much to me as a youngster. Drawing Michelangelo those many Saturdays or Sundays in the 1960s was like a whistle-stop tour around great sculptures; the fact they were not the real McCoy meant nothing to me.

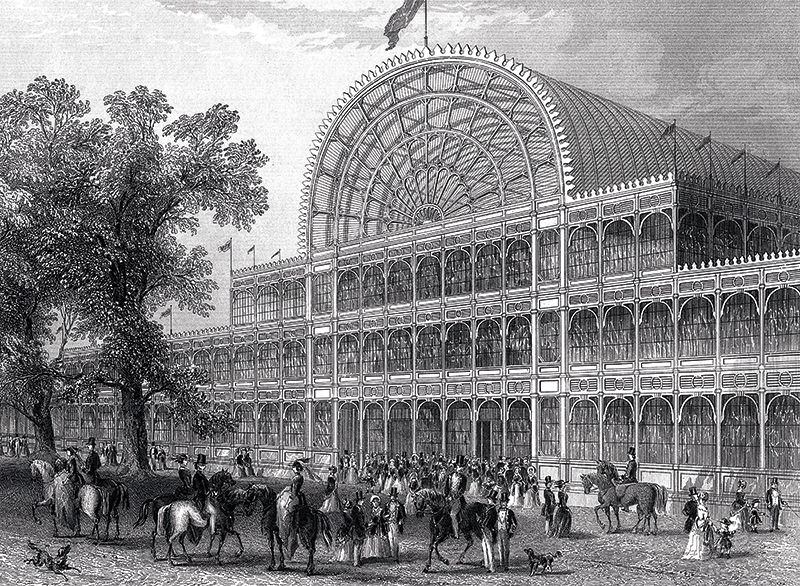

Credit: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

The sense of crowding history and art into this vast room is amplified today because thousands more people visit now. A tide of people greets you, whereas I remember it as a bit of a dusty old place where I would be left to wander about, almost on my own. I loved the kind of mad array in the whole museum, as if little thought has been given to its arrangement, and that feeling is still there. It’s like a storehouse, not necessarily carefully arranged. I’m sure the curators would disagree but I get the feeling of creative jumble: it’s too, too much to take in at any one visit.

But of course the crying shame about most museums is that much of it is the booty of empire, got as the spoils of being the top dog in the 19th century. Our network of museums would not pass an audit if a just and honest acquisition policy was adhered to. But then the past was not that equitable. And museums are a part of the past.

The V&A owes its creation to the Great Exhibition of 1851 which was put up just north of the museum, in Hyde Park. Millions came from all over and its effect, with the recently opened railway lines, was socially enormous. It pushed tourism up the ladder of polite things to do. And it helped also to put industry and the arts foremost in people’s minds. But it did have a side that I have banged on about for decades: it showed that Great Britain, once the workshop of the world, was losing out to European – and American – innovation. Most of the goods made by British businesses were consumer goods for the growing middle class. There was little evidence of new innovation in business. The new industries were being developed, among other places, in the German states – Germany being not yet a country. Britain was becoming a nation of yesterday’s inventions. Investors were making their money in the colonies and through people shopping. Not in new science and technology.

Top-dog status in the world meant largely military and empire prowess, not technological invention. Britain was laying down many of its later problems, when it became increasingly a land of cheap jobs and an underpaid, often under-skilled, workforce. A multitude of British jobs often left people on the edge of poverty, with politicians and trade unionists struggling to up the wages of the working poor. But also consider the great wealth of the Victorian world that was derived from the opium trade. And the fights that GB had to have, particularly with China to keep open the drug dens servicing the Chinese poor.