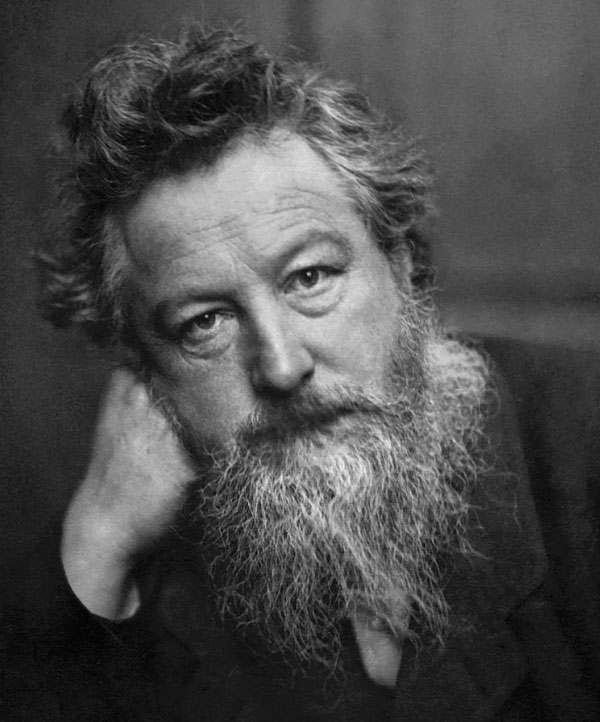

Morris was a part of the revolt against Victorianism and capitalism, and all of the decoration of oppression that it entailed. Hence me hiding myself in his work, a hundred years after Morris graduated from the criticism of Victorianism to revolutionary socialism, was a soft way of still staying engaged in a struggle to change the world, but by being a ‘look-backer’, not an engager in the present.

The mid-to-late 70s, when I tried to hide from the class struggle of the day and the world of Edward Heath (Tory) and Harold Wilson (Labour), was a seismic period. For soon enough the political tables had been overturned and Margaret Thatcher had replaced Heath and James Callaghan had replaced Harold Wilson. We were about to enter the Winter of Discontent, when rubbish due to council worker strikes was piled up on the streets and dead bodies were left unburied. It looked as if the post-war compromise between all political players around full employment, social housing, social security and education was about to be broken open.

In the next decade, Thatcher closed down the largely Victorian-created industries that had been kept alive on government subsidy since the First World War. The Victorian century was being dispensed with at last, when almost all of the following century had been completed. By 1985 the complete gutting of the basic industries that had led to Great Britain’s material ascendancy was complete. Just 15 years were left until the end of the century and the new millennium to sort out a new Great Britain – or United Kingdom as it was increasingly called.

It was only then that I realised that I had done something by chance, by hiding in Victorianism, that would illuminate my work henceforth. That actually burying myself in the minutiae of the Victorian world equipped me with a good overview of the disastrous turn of Victorian investment and industry that would throw up, enlarge and increase the problems that we would encounter in the century that followed.

In short, our current problems were built in a Victorian world. The fact is that Victorian investors created a low-wage economy and did not invest in a new generation of industries that needed a highly educated working class. That the basic industries were left under-invested, so that the older they got the more costly it was to run them. And only state subsidy would keep them going.

When Thatcher’s government closed down these industries, most of them in the North and the Midlands, she created a bigger gap between North and South. That when asked by Lord Willie Whitelaw “What do you do with nearly a million out of work, suddenly?”, she answered, “Let them have benefit.” The North was broken, and no deeper, newer, educationally inspired investment went into it.

That it was the Tories and not Labour who did the closing down should have meant the North would stay Labour forever. But recently the sense that they were left behind, and eventually Brexit-minded, meant that the North politically rallied to the party that had so changed the environment of the North that it became like a place of decimation. An irony, some might say.

That 78 per cent of money lent by our banks is for the buying and selling of property means that old Victorian investment habits die hard. Who wants to invest in new businesses when you can make a killing in property, putting enormous pressure on today’s housing market.

I could go on. We live in a Victorian-created world. And we need to move on from it. I’m glad I buried myself in Victorianism, for it showed me how long-echoed their influence was. And how much work needs to be done to create a deeper wealth that is not based on low wages and low educational attainments. We need a brilliantly inspired education to change our Victorian times.

John Bird is the founder of The Big Issue